CLOSE

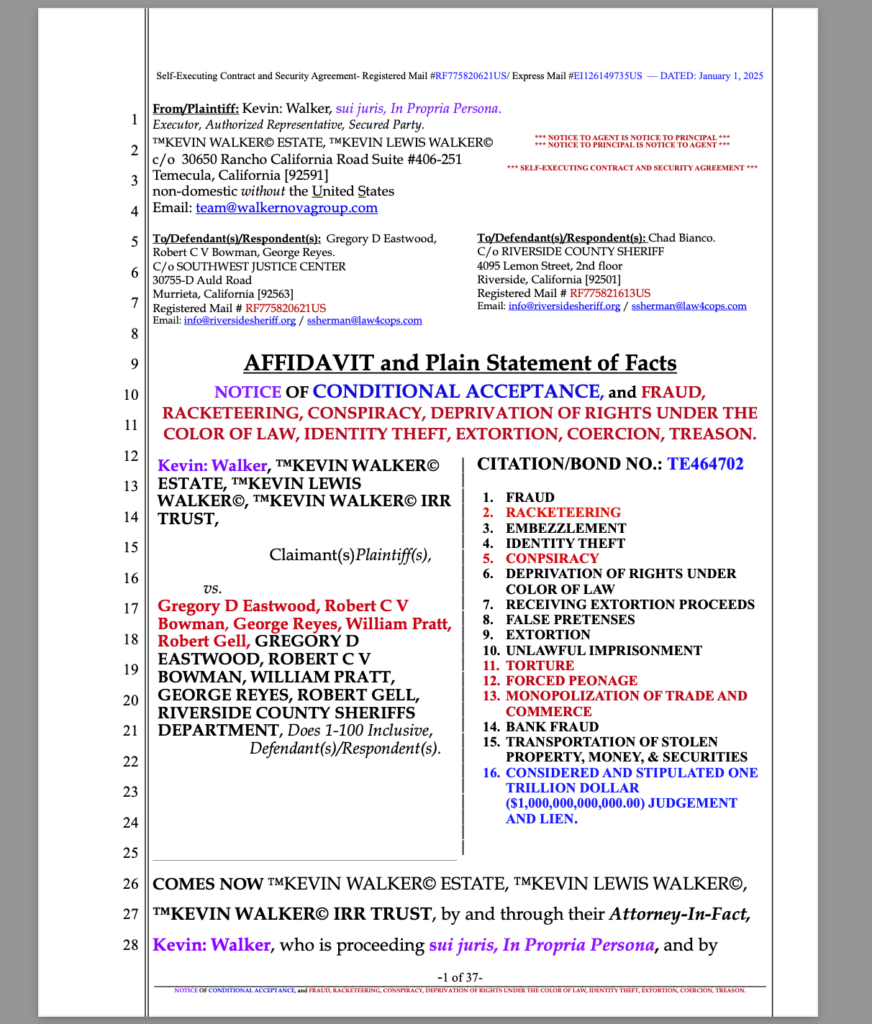

Riverside county Sheriff deputies Gregory D Eastwood and Robbert C V Bowman stalked national and private attorney-in-fact Kevin L. Walker through his neighborhood around the corner from his home and then arrest him on a bogus warrant, and tow his Lamborghini. — There is now an administrative process taking place and a pending One Trillion Dollar ($1,000,000,000,000.00 ) Federal conspiracy, fraud, forced peonage, racketeering lawsuit pending against the deputies and Riverside County Sheriff Department.

LAWSUIT PENDING and will be filed at the end of the administrative process if the right thing is not done.

Riverside County Sheriff deputies Gregory D. Eastwood and Robbert C. V. Bowman stalked national and private attorney-in-fact Kevin L. Walker through his neighborhood around the corner from his home and then arrested him on a bogus warrant, towing his Lamborghini. There is now an administrative process taking place and a pending One Trillion Dollar ($1,000,000,000,000.00) Federal conspiracy, fraud, forced peonage, and racketeering lawsuit against the deputies and the Riverside County Sheriff Department.

Under the Clearfield Doctrine, articulated in Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363 (1943), when governments engage in commercial transactions, they shed their sovereign immunity and are subject to the same rules and liabilities as private corporations. By issuing citations, traffic tickets, and engaging in revenue-generating activities through enforcement mechanisms like towing private automobiles, municipalities and their agents act as corporate entities rather than sovereign bodies. This doctrine underscores that Riverside County and its Sheriff’s Department are not immune from commercial accountability when their actions violate constitutional rights or private contracts.

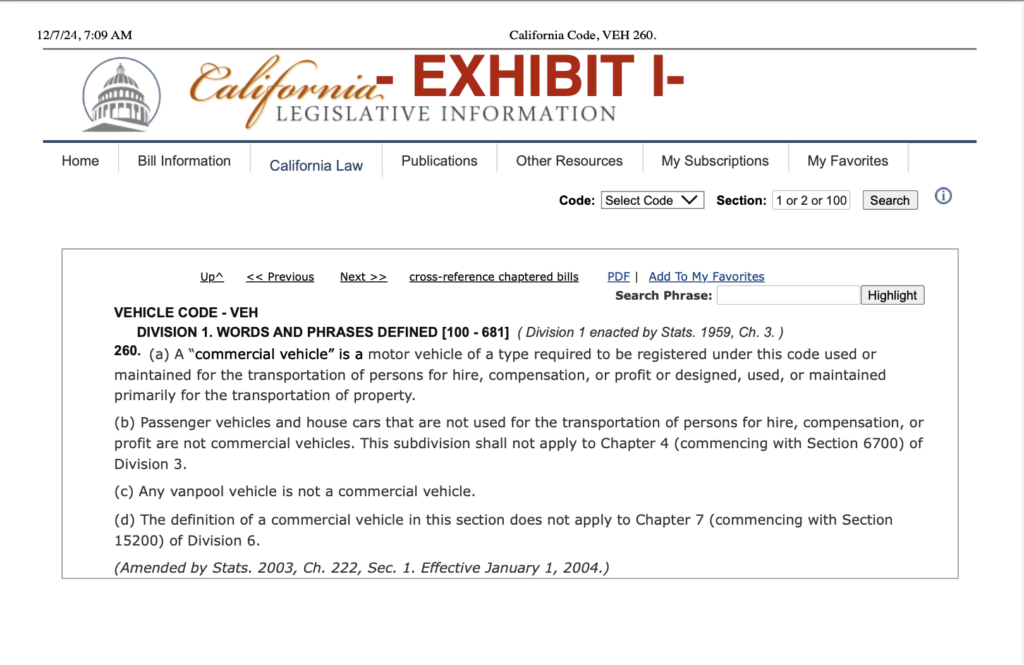

Under California Vehicle Code § 260, only “commercial vehicles” are required to be registered. A “commercial vehicle” is defined as a motor vehicle used or maintained for transporting persons for hire, compensation, or profit, or for the transportation of property. The California DMV further distinguishes between “motor vehicles” and “automobiles,” with the latter commonly referring to private, personal modes of transportation not used for commercial purposes. As such, private automobiles, when not engaged in commerce or profit-driven activities, do not meet the statutory definition of a “commercial vehicle” and are therefore not subject to mandatory registration requirements under this code.

California Vehicle Code § 4000 applies specifically to “motor vehicles,” which are defined as vehicles used in commerce for transporting persons or property for profit. This distinction excludes private automobiles, which are personal-use conveyances not engaged in commercial activities. Courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, have upheld the fundamental right to travel on public highways without unreasonable government interference, recognizing that private travel is distinct from regulated commercial activity. Case law such as Thompson v. Smith affirms this right, and statutory interpretation limits the term “motor vehicle” to vehicles used in commerce, making the registration requirement inapplicable to private automobiles.

The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) provides additional support that traffic tickets and citations operate as offers to contract:

Additionally, under 22 CFR § 72.11, all crimes are commercial in nature. This regulation aligns with the fact that traffic citations are revenue-generating instruments issued by corporate entities (municipalities), which operate with an EIN like any other corporation.

The unlawful stop, detainment, and subsequent actions of the Defendants/Respondents are in violation of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States and constitute an unlawful seizure. The fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine, as articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court, establishes that any evidence obtained as a result of an unlawful stop or detainment is tainted and inadmissible in any subsequent proceedings.

The unlawful actions of Gregory D. Eastwood and Robbert C. V. Bowman, including but not limited to the issuance of fraudulent citations/contracts under threat, duress, and coercion, render all actions and evidence derived therefrom void ab initio. See Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963).

Enter your account data and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Here you'll find all collections you've created before.